January 23 2023

by Conor Gallagher

Washington is reportedly pushing a deal with Ankara that would see the US sell Türkiye F-16s (which it has been requesting the past two years), and in exchange Türkiye would forgo any military incursion into northern Syria and would agree to the admission of Finland and Sweden to NATO.

It’s unlikely this will meet Türkiye’s price as Ankara has demanded that Sweden stop supporting what Türkiye deems to be Kurdish terrorists and made specific requests, including extraditions. Sweden has said it will not meet these demands, and the Quran-burning protests against Türkiye in Stockholm on Saturday almost certainly made it politically untenable for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to agree to any deal ahead of what’s expected to be a tight election on May 14.

Additionally, any deal would likely need to include promises from Washington to scale back its military support for Greece, such as its planned F-35 sale. As the following post illustrates, Washington is also using contested waters in the eastern Mediterranean as another pressure point and is likely to escalate there if Erdogan doesn’t relent on Sweden’s NATO bid and back off in Syria.

***

The race to drill and bring to market natural gas in the eastern Mediterranean Sea has taken on additional importance ever since Europe decided to cut itself off from its main supplier in Russia. The rush for underwater natural gas comes at a time when the US is heavily arming Greece and Cyprus in an effort to pressure Türkiye into falling in line on Washington-led policies on Russia and NATO.

Disagreements over waters and exploratory rights have brought Greece and Türkiye to the brink of conflict recently, and as more gas fields are discovered and the US inserts itself on the side of Athens, conflict is becoming increasingly likely.

The following is a rundown of Greek, Turkish, and Cypriot competing claims and the current situation in the race for eastern Mediterranean gas.

***

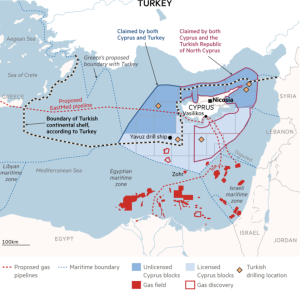

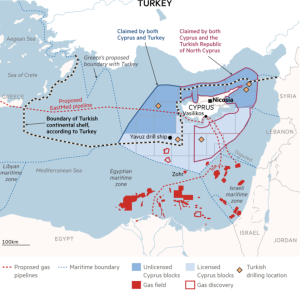

Last year saw new gas discoveries off Cyprus, including an estimated 70 billion cubic meters (bcm) field and a 57-84 bcm field. The finds raise the possibility of the island country finally becoming a gas exporter; it also raises the possibility of conflict as Türkiye, Greece, and Cyprus have wide-ranging disagreements over maritime boundaries.

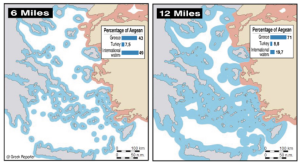

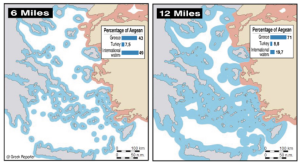

Greece argues that its islands in the Aegean sea can generate their own Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) which would allow Greece to explore more than 200 nautical miles. Türkiye has argued that islands can not generate their own EEZs and that Greece’s EEZ should start from its mainland, rather than from each of its hundreds of islands.

Under the UN’s Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), every state has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles. Türkiye, however, is not a signatory to UNCLOS and does not agree with the rights of the Aegean islands to such a distance. Ankara has threatened Athens with military action should it extend its waters. Both Greece and Türkiye currently claim six nautical miles off of their territory in Aegean and 12 nautical miles off their other shores.

While the EEZ governed by UNCLOS allows trading ships to pass freely, the passage of military naval ships is highly contested and Türkiye is threatened by the possibility of having to ask Greece permission for military navigation. Should Greece extend its EEZ to 12 nautical miles off its Aegean islands, it would make a drastic difference:

Six nautical miles have been in force since 1936. Tensions over the 12 nautical mile question ran highest between the two countries in the 1990s when UNCLOS was coming into force. In 1995, the Turkish Parliament officially declared that unilateral action by Greece to extend the Aegean islands to 12 nautical miles would constitute a casus belli, a position Ankara maintains today.

Well now Greece says that in March it’s going to extend its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles off of the island of Crete, which also happens to host a US naval base at Souda Bay. The US and Greece are also upgrading and expanding the facility with the goal to transform it into a permanent base for part of the Hellenic Navy, in order to facilitate faster and more direct access to the Eastern Mediterranean.

The move is reportedly being driven by ExxonMobil efforts to drill for natural gas and oil to the west and southwest of Crete. The Greek daily Kathimerini reported last week that ExxonMobil, in partnership with Greece’s HELLENiQ Energy, will push ahead with its search for natural gas and oil to the west and southwest of Crete despite Turkish opposition, fueling further suspicion in Ankara that the US is trying to punish the NATO member for its refusal to join the bloc’s aggressive approach against Russia.

US Arms Add Fuel to Fire

For decades the US acted as an impartial mediator between Greece, Türkiye, and Cyprus. Greece and Türkiye came close to military conflict in 1987, 1996 and in 2020, the last of which was over an accident when a Greek and a Turkish warship were involved in a minor collision during a standoff in the eastern Mediterranean. NATO stepped in in 1987 and in 1996 to help both sides cool off, and in 2020, Germany, which had the rotating presidency of the EU, took on the role of mediator.

The US is neutral no more. NATO’s war in Ukraine has brought long-festering issues between Ankara and Washington out into the open. The disagreements include US support of Kurds in Syria, Türkiye blocking Sweden’s NATO bid, Ankara’s refusal to open the Dardanelles to NATO warships, US sanctions and threat of sanctions, Washington’s refusal to extradite a cleric Türkiye blames for a 2016 coup attempt, Ankara’s purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems, Türkiye’s refusal to apply sanctions on Russia, and Ankara’s overall unwillingness to follow orders from Washington.

The US is now providing strong backing for Greece, which is clearly meant to send a message to Erdogan – at least that’s the belief inside Türkiye. Hasan Koni, a scholar on strategic studies at Istanbul Kultur University, told Türkiye’s Anadolu Agency::

The American security apparatus has also recognized that the balance of power in the region is shifting toward Türkiye and needs to be “checked by empowering Greece,” he said, adding that Washington’s push for more Greek bases is aimed at “containing Türkiye.”

The US has backed Greece despite the risk of a full break with Türkiye – the most important member of NATO due to its control of the Dardanelles and access to the Black Sea, as well as its second largest standing army in NATO.

Last year Greece deployed US-donated armored vehicles on the islands of Lesbos, Chios, and Samos, which is in violation of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty. Ankara is also enraged about Greece’s militarization of islands within sight of Türkiye’s western coast, such as the Dodecanese chain that includes Rhodes.

There have been reports of Greek military exercises involving tanks, artillery and attack helicopters being held on Rhodes and Lesbos. Ankara has issued protests through diplomatic channels to both Athens and Washington and sent letters of complaint to the UN, all to no avail.

The US is also proposing to the Greek armed forces to replace all Russian-made military equipment including air defense systems with new military equipment produced by the US, including US Patriot missiles, which is a slap in Türkiye’s face.

Beginning during the Gulf War, Türkiye asked NATO multiple times to deploy early warning systems and Patriot missiles to Türkiye, but was always turned down. US security experts Jim Townsend and Rachel Ellehus explained it like this:

Long suspicious that NATO did not appreciate Türkiye’s vulnerability in such a dangerous neighborhood, Ankara came to view its missile defense requests as a litmus test for how much NATO really cared about Türkiye.

Ankara didn’t like the answer to that litmus test. Türkiye felt ignored by its western partners as its EU membership was all but dead, and it wasn’t getting the military hardware it requested. In 2017 Türkiye turned to Russia. It purchased Russian S-400 missile defense systems, which only further strained ties with NATO.

In December, a consortium of Italy’s Eni and France’s TotalEnergies found more natural gas off Cyprus. The Greek Cypriot administration’s exploration program is also disputed by Türkiye, which claims overlapping jurisdictions either on its own continental shelf or in the waters of the Republic of Northern Cyprus. Cyprus is split between the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus in the south and the Turkish Republic of Cyprus in the north, which is recognized only by Ankara.

The US, wanting to keep the peace in NATO between Greece and Türkiye, had a decades-old policy of favoring negotiations on divided Cyprus and often acted as a mediator between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots.

But In September the Biden administration lifted the 35-year-old ban on the sale of US arms to the Republic of Cyprus. Congress restricted the sale of U.S. arms to Cyprus in 1987, hoping it would incentivize a diplomatic settlement to the island’s conflict.

Cyprus was required to block Russian naval vessels from accessing its ports in order to get the US arms sale ban lifted. Türkiye already has about 40,000 troops on the island, and Erdogan recently declared plans to reinforce them with land, naval and aerial weapons, ammunition and vehicles.

The decades’ old and UN-sanctioned principle of a bizonal, bicommunal federation on Cyprus has now broken down in favor of a two-state solution.

Despite the mad rush for Mediterranean gas in the wake of Europe and Russia schism, it still will not come close to replacing the amount that was piped in from Russia and requires rapid expansion of liquefaction capabilities, the connection of Israeli and Cypriot gas fields to such facilities, and/or implement pipelines, all of which will take years.

The EastMed Pipeline

The Trump administration backed a gas pipeline that would connect Israeli and Cypriot offshore gas fields to Greece and Italy. From there it would be shipped to the rest of Europe. The EastMed pipeline would have been the world’s longest (1,900 kilometers) and deepest underwater pipeline, initially providing 9-12 billion cubic meters annually.

One problem with the plan, however, was that it excluded Türkiye. In response, Erdogan opted to pursue Türkiye’s self-interest in gas through aggressive offshore oil exploration in disputed waters claimed by Cyprus. Turkish war vessels accompanied its drill ships near Cyprus, resulting in standoffs with Greek and French naval fleets. Ankara also began signing agreements with the government in Tripoli. From Dr Othon Anastasakis, Director of the European Studies Centre at the University of Oxford:

In November 2019, in response to Greece’s backing of the Mediterranean Gas Forum with Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Italy and Jordan, Türkiye signed a maritime agreement with Libya that cuts a corridor across the Aegean to demarcate new maritime boundaries, with the proposed line in this accord running close to the eastern side of the island of Crete. On October 3, 2022, Ankara signed a follow up preliminary agreement with the Tripoli government to explore for oil and gas off the Libyan coast without specifying whether the surveys would take place in waters south of Greece. In effect, Libya has become an important third actor in the bilateral dispute between Greece and Türkiye and relations between the Athens and Tripoli governments have suffered a major blow as a result.

In January 2022, the Biden Administration abruptly halted American support of EastMed. Israeli and even some American officials were reportedly surprised by the sudden decision as the State Department did not appear to have adequately consulted with Cyprus, Greece, and Israel ahead of time. Additionally, Biden was a vocal supporter of the project during his time as Obama VP, and the US position was consistently that Europe needed to wean itself off of Russian natural gas.

The US government and American private sector were not directly involved in the pipeline project (the agreement was signed in January 2020 by the governments of Israel, Greece, and Cyprus), but as Henri Barkey, an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told the National:

American support always affects a good housekeeping seal. When you have American buy-in, it’s easier for banks to provide financing for more countries to be interested. In that sense, what the US says is important.

US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria “Fuck the EU” Nuland has taken an active role in the Eastern Mediterranean and had this to say about the pipeline:

“Frankly, we don’t have 10 years, but in 10 years from now, we want to be far, far more green and far more diverse” in energy sources, Nuland said. “So what we’re looking for within the hydrocarbon context are options that can get us more gas, more oil for this short transition period.”

That short transition period also happens to rely heavily on US exports of LNG.

In November Greece canceled the long-planned privatization for the Alexandroupolis port with Mitsotakis declaring it too precious of a resource to relinquish. Instead the US military has set up shop there, using it as an entry point to funnel weapons to Ukraine. There are also plans in the works to create a floating gas storage and regasification unit at the port, which will be serviced by American LNG supplies. A pipeline from Alexandroupolis is also planned to send that gas north to the Balkans.

Washington is reportedly pushing a deal with Ankara that would see the US sell Türkiye F-16s (which it has been requesting the past two years), and in exchange Türkiye would forgo any military incursion into northern Syria and would agree to the admission of Finland and Sweden to NATO.

It’s unlikely this will meet Türkiye’s price as Ankara has demanded that Sweden stop supporting what Türkiye deems to be Kurdish terrorists and made specific requests, including extraditions. Sweden has said it will not meet these demands, and the Quran-burning protests against Türkiye in Stockholm on Saturday almost certainly made it politically untenable for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to agree to any deal ahead of what’s expected to be a tight election on May 14.

Additionally, any deal would likely need to include promises from Washington to scale back its military support for Greece, such as its planned F-35 sale. As the following post illustrates, Washington is also using contested waters in the eastern Mediterranean as another pressure point and is likely to escalate there if Erdogan doesn’t relent on Sweden’s NATO bid and back off in Syria.

***

The race to drill and bring to market natural gas in the eastern Mediterranean Sea has taken on additional importance ever since Europe decided to cut itself off from its main supplier in Russia. The rush for underwater natural gas comes at a time when the US is heavily arming Greece and Cyprus in an effort to pressure Türkiye into falling in line on Washington-led policies on Russia and NATO.

Disagreements over waters and exploratory rights have brought Greece and Türkiye to the brink of conflict recently, and as more gas fields are discovered and the US inserts itself on the side of Athens, conflict is becoming increasingly likely.

The following is a rundown of Greek, Turkish, and Cypriot competing claims and the current situation in the race for eastern Mediterranean gas.

***

Last year saw new gas discoveries off Cyprus, including an estimated 70 billion cubic meters (bcm) field and a 57-84 bcm field. The finds raise the possibility of the island country finally becoming a gas exporter; it also raises the possibility of conflict as Türkiye, Greece, and Cyprus have wide-ranging disagreements over maritime boundaries.

Greece argues that its islands in the Aegean sea can generate their own Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) which would allow Greece to explore more than 200 nautical miles. Türkiye has argued that islands can not generate their own EEZs and that Greece’s EEZ should start from its mainland, rather than from each of its hundreds of islands.

Under the UN’s Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), every state has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles. Türkiye, however, is not a signatory to UNCLOS and does not agree with the rights of the Aegean islands to such a distance. Ankara has threatened Athens with military action should it extend its waters. Both Greece and Türkiye currently claim six nautical miles off of their territory in Aegean and 12 nautical miles off their other shores.

While the EEZ governed by UNCLOS allows trading ships to pass freely, the passage of military naval ships is highly contested and Türkiye is threatened by the possibility of having to ask Greece permission for military navigation. Should Greece extend its EEZ to 12 nautical miles off its Aegean islands, it would make a drastic difference:

Six nautical miles have been in force since 1936. Tensions over the 12 nautical mile question ran highest between the two countries in the 1990s when UNCLOS was coming into force. In 1995, the Turkish Parliament officially declared that unilateral action by Greece to extend the Aegean islands to 12 nautical miles would constitute a casus belli, a position Ankara maintains today.

Well now Greece says that in March it’s going to extend its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles off of the island of Crete, which also happens to host a US naval base at Souda Bay. The US and Greece are also upgrading and expanding the facility with the goal to transform it into a permanent base for part of the Hellenic Navy, in order to facilitate faster and more direct access to the Eastern Mediterranean.

The move is reportedly being driven by ExxonMobil efforts to drill for natural gas and oil to the west and southwest of Crete. The Greek daily Kathimerini reported last week that ExxonMobil, in partnership with Greece’s HELLENiQ Energy, will push ahead with its search for natural gas and oil to the west and southwest of Crete despite Turkish opposition, fueling further suspicion in Ankara that the US is trying to punish the NATO member for its refusal to join the bloc’s aggressive approach against Russia.

US Arms Add Fuel to Fire

For decades the US acted as an impartial mediator between Greece, Türkiye, and Cyprus. Greece and Türkiye came close to military conflict in 1987, 1996 and in 2020, the last of which was over an accident when a Greek and a Turkish warship were involved in a minor collision during a standoff in the eastern Mediterranean. NATO stepped in in 1987 and in 1996 to help both sides cool off, and in 2020, Germany, which had the rotating presidency of the EU, took on the role of mediator.

The US is neutral no more. NATO’s war in Ukraine has brought long-festering issues between Ankara and Washington out into the open. The disagreements include US support of Kurds in Syria, Türkiye blocking Sweden’s NATO bid, Ankara’s refusal to open the Dardanelles to NATO warships, US sanctions and threat of sanctions, Washington’s refusal to extradite a cleric Türkiye blames for a 2016 coup attempt, Ankara’s purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems, Türkiye’s refusal to apply sanctions on Russia, and Ankara’s overall unwillingness to follow orders from Washington.

The US is now providing strong backing for Greece, which is clearly meant to send a message to Erdogan – at least that’s the belief inside Türkiye. Hasan Koni, a scholar on strategic studies at Istanbul Kultur University, told Türkiye’s Anadolu Agency::

The American security apparatus has also recognized that the balance of power in the region is shifting toward Türkiye and needs to be “checked by empowering Greece,” he said, adding that Washington’s push for more Greek bases is aimed at “containing Türkiye.”

The US has backed Greece despite the risk of a full break with Türkiye – the most important member of NATO due to its control of the Dardanelles and access to the Black Sea, as well as its second largest standing army in NATO.

Last year Greece deployed US-donated armored vehicles on the islands of Lesbos, Chios, and Samos, which is in violation of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty. Ankara is also enraged about Greece’s militarization of islands within sight of Türkiye’s western coast, such as the Dodecanese chain that includes Rhodes.

There have been reports of Greek military exercises involving tanks, artillery and attack helicopters being held on Rhodes and Lesbos. Ankara has issued protests through diplomatic channels to both Athens and Washington and sent letters of complaint to the UN, all to no avail.

The US is also proposing to the Greek armed forces to replace all Russian-made military equipment including air defense systems with new military equipment produced by the US, including US Patriot missiles, which is a slap in Türkiye’s face.

Beginning during the Gulf War, Türkiye asked NATO multiple times to deploy early warning systems and Patriot missiles to Türkiye, but was always turned down. US security experts Jim Townsend and Rachel Ellehus explained it like this:

Long suspicious that NATO did not appreciate Türkiye’s vulnerability in such a dangerous neighborhood, Ankara came to view its missile defense requests as a litmus test for how much NATO really cared about Türkiye.

Ankara didn’t like the answer to that litmus test. Türkiye felt ignored by its western partners as its EU membership was all but dead, and it wasn’t getting the military hardware it requested. In 2017 Türkiye turned to Russia. It purchased Russian S-400 missile defense systems, which only further strained ties with NATO.

In December, a consortium of Italy’s Eni and France’s TotalEnergies found more natural gas off Cyprus. The Greek Cypriot administration’s exploration program is also disputed by Türkiye, which claims overlapping jurisdictions either on its own continental shelf or in the waters of the Republic of Northern Cyprus. Cyprus is split between the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus in the south and the Turkish Republic of Cyprus in the north, which is recognized only by Ankara.

The US, wanting to keep the peace in NATO between Greece and Türkiye, had a decades-old policy of favoring negotiations on divided Cyprus and often acted as a mediator between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots.

But In September the Biden administration lifted the 35-year-old ban on the sale of US arms to the Republic of Cyprus. Congress restricted the sale of U.S. arms to Cyprus in 1987, hoping it would incentivize a diplomatic settlement to the island’s conflict.

Cyprus was required to block Russian naval vessels from accessing its ports in order to get the US arms sale ban lifted. Türkiye already has about 40,000 troops on the island, and Erdogan recently declared plans to reinforce them with land, naval and aerial weapons, ammunition and vehicles.

The decades’ old and UN-sanctioned principle of a bizonal, bicommunal federation on Cyprus has now broken down in favor of a two-state solution.

Despite the mad rush for Mediterranean gas in the wake of Europe and Russia schism, it still will not come close to replacing the amount that was piped in from Russia and requires rapid expansion of liquefaction capabilities, the connection of Israeli and Cypriot gas fields to such facilities, and/or implement pipelines, all of which will take years.

The EastMed Pipeline

The Trump administration backed a gas pipeline that would connect Israeli and Cypriot offshore gas fields to Greece and Italy. From there it would be shipped to the rest of Europe. The EastMed pipeline would have been the world’s longest (1,900 kilometers) and deepest underwater pipeline, initially providing 9-12 billion cubic meters annually.

One problem with the plan, however, was that it excluded Türkiye. In response, Erdogan opted to pursue Türkiye’s self-interest in gas through aggressive offshore oil exploration in disputed waters claimed by Cyprus. Turkish war vessels accompanied its drill ships near Cyprus, resulting in standoffs with Greek and French naval fleets. Ankara also began signing agreements with the government in Tripoli. From Dr Othon Anastasakis, Director of the European Studies Centre at the University of Oxford:

In November 2019, in response to Greece’s backing of the Mediterranean Gas Forum with Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Italy and Jordan, Türkiye signed a maritime agreement with Libya that cuts a corridor across the Aegean to demarcate new maritime boundaries, with the proposed line in this accord running close to the eastern side of the island of Crete. On October 3, 2022, Ankara signed a follow up preliminary agreement with the Tripoli government to explore for oil and gas off the Libyan coast without specifying whether the surveys would take place in waters south of Greece. In effect, Libya has become an important third actor in the bilateral dispute between Greece and Türkiye and relations between the Athens and Tripoli governments have suffered a major blow as a result.

In January 2022, the Biden Administration abruptly halted American support of EastMed. Israeli and even some American officials were reportedly surprised by the sudden decision as the State Department did not appear to have adequately consulted with Cyprus, Greece, and Israel ahead of time. Additionally, Biden was a vocal supporter of the project during his time as Obama VP, and the US position was consistently that Europe needed to wean itself off of Russian natural gas.

The US government and American private sector were not directly involved in the pipeline project (the agreement was signed in January 2020 by the governments of Israel, Greece, and Cyprus), but as Henri Barkey, an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told the National:

American support always affects a good housekeeping seal. When you have American buy-in, it’s easier for banks to provide financing for more countries to be interested. In that sense, what the US says is important.

US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria “Fuck the EU” Nuland has taken an active role in the Eastern Mediterranean and had this to say about the pipeline:

“Frankly, we don’t have 10 years, but in 10 years from now, we want to be far, far more green and far more diverse” in energy sources, Nuland said. “So what we’re looking for within the hydrocarbon context are options that can get us more gas, more oil for this short transition period.”

That short transition period also happens to rely heavily on US exports of LNG.

In November Greece canceled the long-planned privatization for the Alexandroupolis port with Mitsotakis declaring it too precious of a resource to relinquish. Instead the US military has set up shop there, using it as an entry point to funnel weapons to Ukraine. There are also plans in the works to create a floating gas storage and regasification unit at the port, which will be serviced by American LNG supplies. A pipeline from Alexandroupolis is also planned to send that gas north to the Balkans.

No comments:

Post a Comment