Death In Art

Memento Mori, vanitas, mortality — death is one of the most pervasive themes in art history. While many artworks celebrate afterlives in heaven or hell, death is most often referenced as grim reminder of numbered days, and a powerful motivator to live well while you can. Every culture has rituals surrounding death, appearing in artwork as icons and colors. Hourglasses and wilted flowers for the Dutch, the Cuckoo bird in Japan, the Totenkopf in Germany.30 Ways To Describe An Owl According to Kenojuak Ashevak

Source: Inuit Art

May 21 2020

Kenojuak Ashevak was born in an igloo in an Inuit camp, Ikirasaq, at the southern coast of Baffin Island. Her father, Ushuakjuk, an Inuit hunter and fur trader, and her mother, Silaqqi, named Kenojuak after Silaqqi's deceased father.

|

| Baffin Island |

According to this Inuit naming tradition, the love and respect that had been accorded to her during her lifetime would now pass on to their daughter.

Kenojuak also had a brother and a sister. Kenojuak remembered Ushuakjuk as "a kind and benevolent man." Her father, a respected shaman, "had more knowledge than average mortals, and he would help all the Inuit people." According to Kenojuak, her father believed he could predict weather, predict good hunting seasons and even turn into a walrus; he also had the ability "to make fish swarm at the surface so it was easier to fish."[citation needed] Her father came into conflict with Christian converts, and some enemies assassinated him in a hunting camp in 1933, when she was only six.

After her father's murder, Kenojuak moved with her widowed mother Silaqqi and the rest of the family to the home of Silaqqi's mother, Koweesa, who taught her traditional crafts, including the repair of sealskins for trade with the Hudson's Bay Company and how to make waterproof clothes sewn with caribou sinew.

When she was 19, her mother, Silaqqi, and stepfather, Takpaugni, arranged for her to marry Johnniebo Ashevak (1923–1972), a local Inuit hunter. Kenojuak was reluctant, she said, even playfully throwing pebbles at him when he would approach her.

In time, however, she came to love him for his kindness and gentleness, a man who developed artistic talents in his own right and who sometimes collaborated with her on projects; the National Gallery of Canada holds two of Johnniebo's works, Taleelayo with Sea Bird (1965) and Hare Spirits (1960).[6] In 1950 a public health nurse arrived in her Arctic village; Kenojuak, having tested positive in a tuberculosis screening, was sent against her will to Parc Savard hospital in Quebec City, where she stayed for over three years, from early 1952 to the summer of 1955. She had just given birth when she was forcib

In 1966, Kenojuak and Johnniebo moved to Cape Dorset. Many of their children and grandchildren succumbed to disease, as did her husband after 26 years of marriage. Three daughters of Kenojuak, Mary, Elisapee Qiqituk, and Aggeok, died in childhood, and four sons, Jamasie, her adopted son Ashevak, and Kadlarjuk and Qiqituk. The latter two were adopted at birth by another family.

The year after Johnniebo died in 1972, Kenojuak remarried, to Etyguyakjua Pee; he died in 1977. In 1978 she married Joanassie Igiu. She had 11 children by her first husband and adopted five more; seven of her children died in childhood. At the time of her death from lung cancer, she was living in a wood-frame house in Kinngait (Cape Dorset).

Kenojuak Ashevak Audacious Owl (1993)

Throughout Kenojuak Ashevak’s (1927-2013) illustrious career, the owl was a constant source of inspiration. In over 100 different prints, Ashevak captured the inquisitive expressions and majestic grandeur of owls using a wide range of vivid colours. What’s also impressive is the fact that each of these prints has a creative title to describe her hootiful creations. Below are our 30 favourite ways to describe a Kenojuak Ashevak owl.

AUDACIOUS OWL (1993)

Look at that owl strut – no wonder Ashevak named this stonecut print the Audacious Owl! Although Ashevak uses more muted colours here compared to her earlier owls, the expansive plumage captures the boldness of this bird.

Kenojuak Ashevak Autumnal Owl (1999)

AUTUMNAL OWL (1999)

“I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers.” – L.M. Montgomery and this owl, probably. Ashevak’s Autumnal Owl is highlighted by the warm orange and red tones of the owl’s feathers that reflect the hues of the season.

Kenojuak Ashevak Blossoming Owl (2006)

BLOSSOMING OWL (2006)

Flower power! Blossoming Owl is sprouting flora where its wings and ears should be, building an insulating wall of foliage between itself and the edges of the page. This print was one of five serigraphs commissioned from Ashevak by the Inuit Gallery of Vancouver. Predominantly sold to private collectors, these prints are rarely publicly displayed, and never as the set of five they were intended as. Can you figure out which, if any, of the rest of the owls in this post are part of the set?

Kenojuak Ashevak Blue Owl (1969)

BLUE OWL (1969)

As shown in Blue Owl, Ashevak had a great eye for pairing pleasing complementary colours. About the process of selecting colours, in 1980, Ashevak told Jean Blodgett: “The colours are part of an informal system that I have. I select two colours that will go side by side, lining them up, saying that these two look good together. I use that system for my colouring and don’t change it halfway through the drawing.” Although varying shapes and textures are nestled within and behind the bird, the owl’s vivid eyes keep it from fading into the blue.

Kenojuak Ashevak Bright Owl (1967)

BRIGHT OWL (1967)

Owl on the prowl! The negative space and linear emphasis of Bright Owl is characteristic of Ashevak’s work with engraving in the late ‘60s, which was dominated by line drawings that were then etched by Ashevak onto copperplate before being printed. The parallel lines, which here depict feathers, are a repeated motif in other Ashevak engravings from this period, sometimes appearing as hair and fur as well. Ashevak was becoming a bright owl herself during this time: 1967 was the year she became an officer of the Order of Canada.

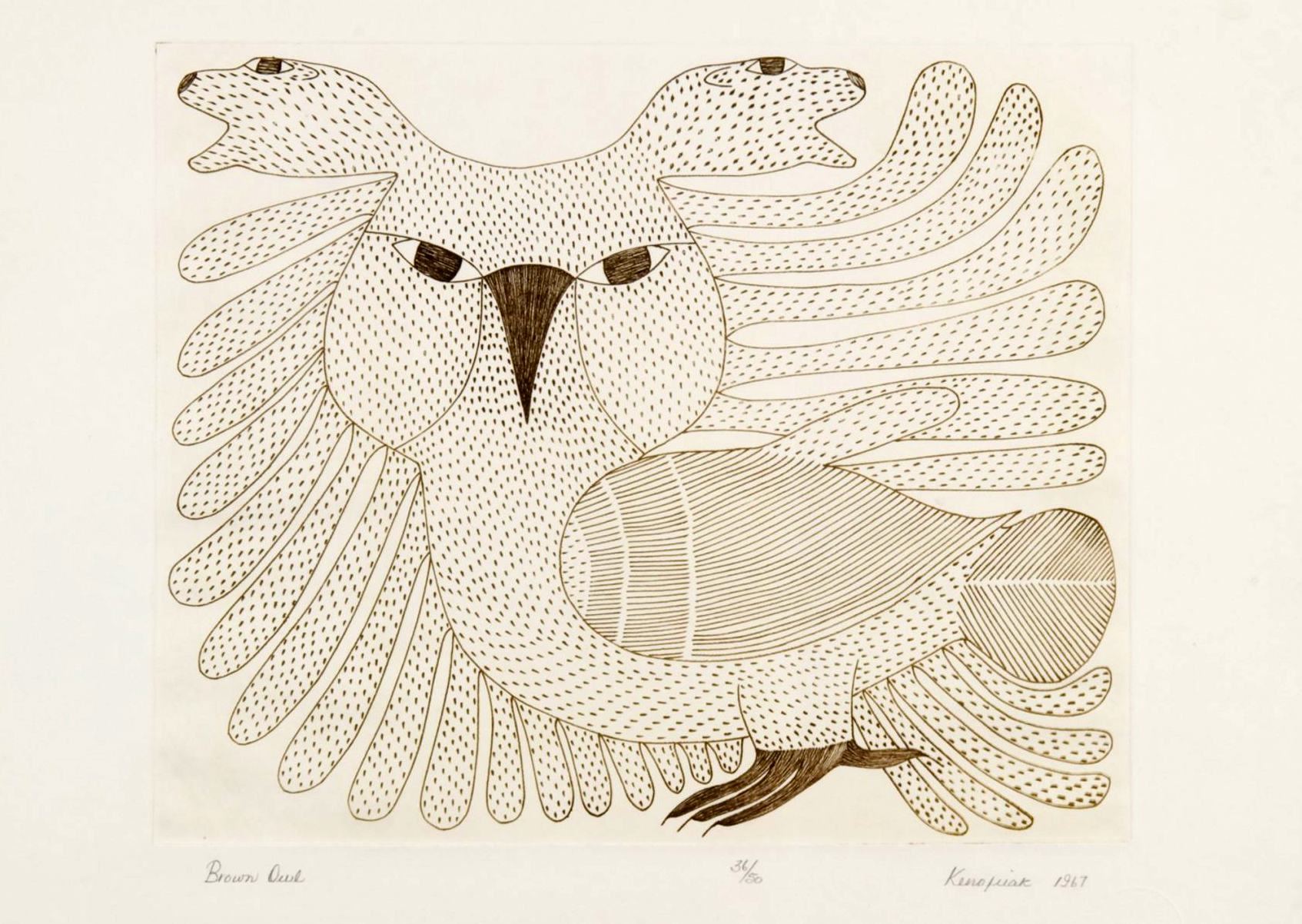

Kenojuak Ashevak Brown Owl (1967)

BROWN OWL (1967)

While the Brown Owl is sparse in colours, it is full of textures. Notice how Ashevak uses varied linework to illustrate the unique plumage of this bird. Look closely and you’ll see two other creatures popping out of this owl’s head.

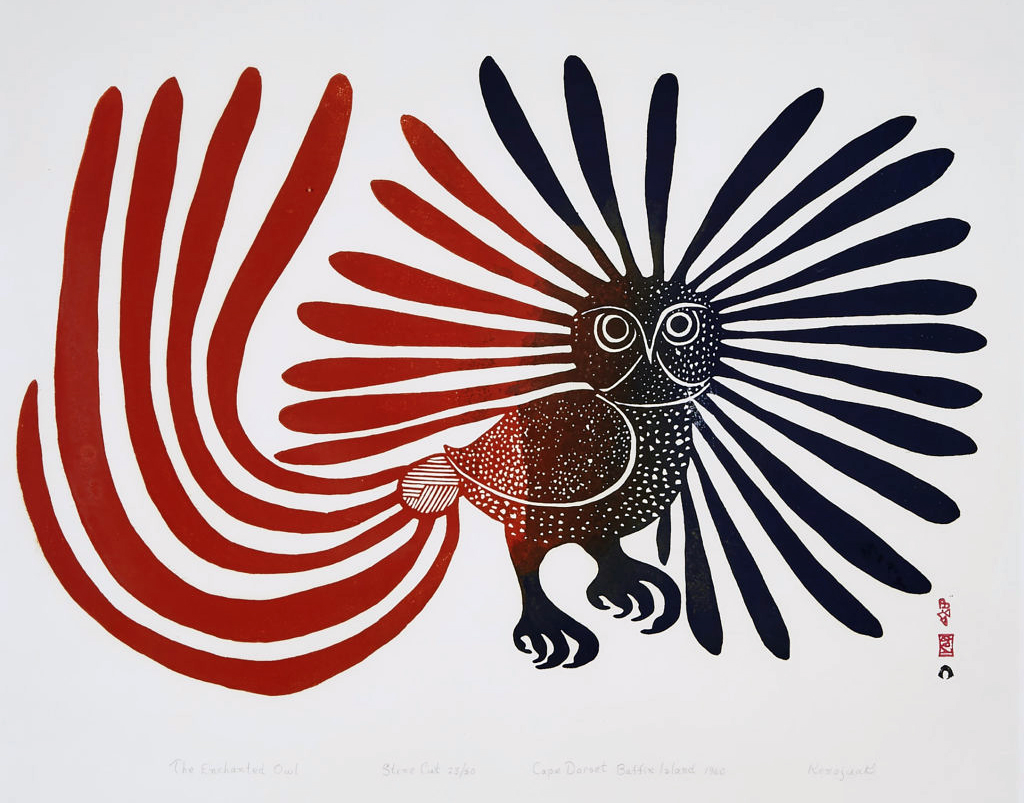

Kenojuak Ashevak The Enchanted Owl (1960)

THE ENCHANTED OWL (1960)

The Enchanted Owl, one of Ashevak’s earliest and most well-known works, depicts an owl that faces out toward the viewer. The texture of the body is created through dots and lines in black and white. The feathers extend out from the body and surround the bird, and the long red tail feathers reach out and curve upwards. Ashevak created a powerful and captivating image through subtle details. In 1970, The Enchanted Owl was reproduced on a Canada Post stamp.

Kenojuak Ashevak Festive Owl (1970)

FESTIVE OWL (1970)

Festive Owl first appeared in the Cape Dorset Print Collection. The black and white image in the print catalogue does not do justice to the reds, browns and greens that compose this stonecut print, which make the abstracted shapes that extend from the owl’s body into oak leaves. Colour is important to reading this piece, but the muted tones definitely seem more restive than festive.

Kenojuak Ashevak Flamboyant Owl (2006)

FLAMBOYANT OWL (2006)

What makes this owl hoot louder than the rest of them? Over the course of her evolution with owl depictions, Ashevak has depicted them sprouting the heads and tails of other animals, surrounded with rainbow plumage, and overlaid on jewel-toned leaves. And yet the almost watery, pastel primary colours of Flamboyant Owl, coupled with its overlarge bunny ears, make it the Prime Minister of this parliament of owls.

Kenojuak Ashevak Grey Owl (1978)

GREY OWL (1978)

50 shades of grey? We don’t think so. Only in its original black-and-white appearance in the 1978 Cape Dorset Print Collection could this owl truly be called ‘grey’. In full colour, it is a tonal riot of browns and greys, with key details, such as the owl’s feet and eyes, picked out in vibrant yellow. Ashevak’s use of symmetry again plays on that idea of boring conventionality, only to subvert it by refusing to let all of the lines of the piece carry the eye outward, instead using the texture of her own hair to subtly throw the balance off.

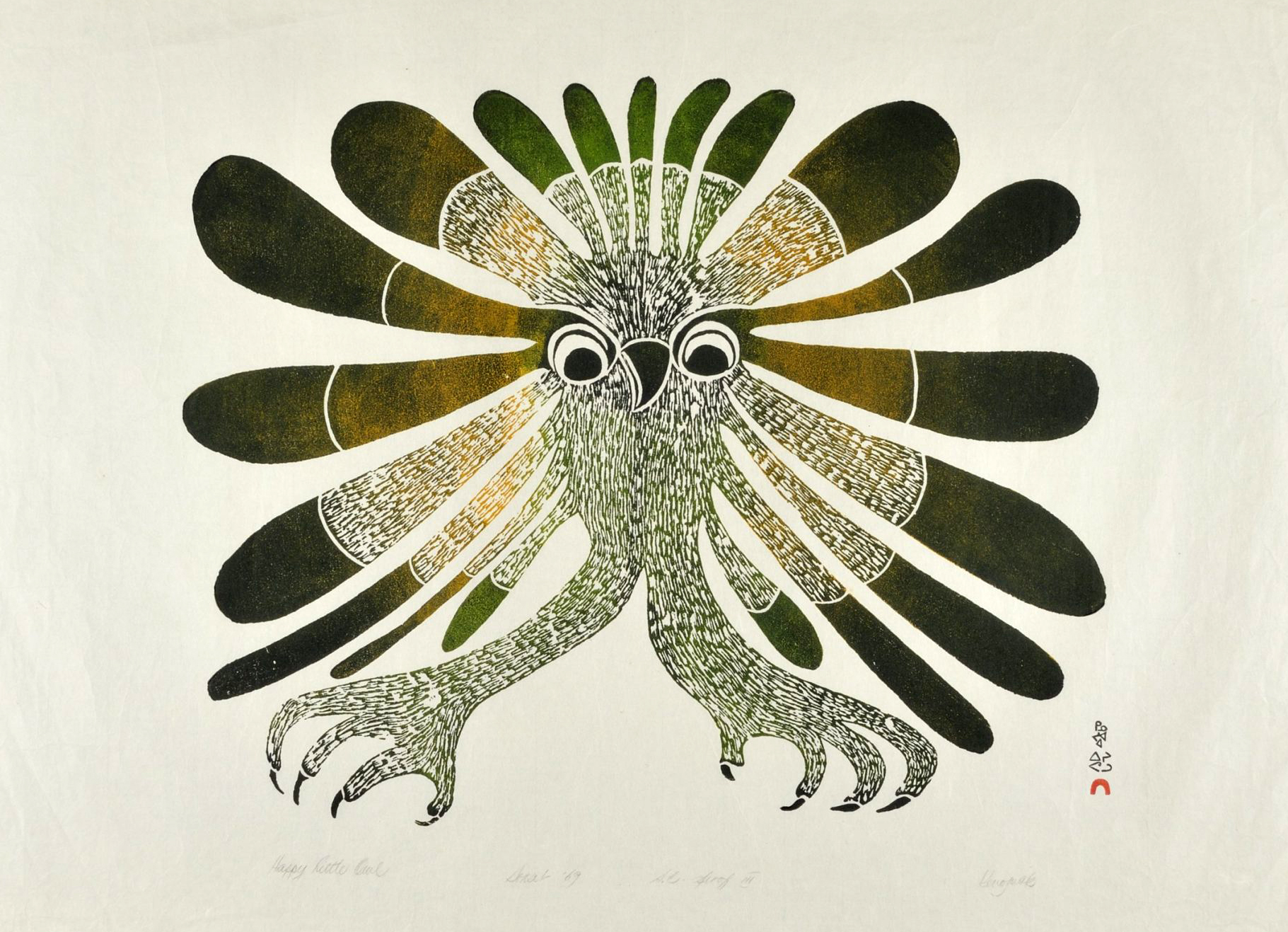

Kenojuak Ashevak Happy Little Owl (1969)

HAPPY LITTLE OWL (1969)

Cover up that sneaky beaky and you could be forgiven for thinking this an abstract starburst. The eyes and beak remain a constant in Ashevak’s owl portraits, regardless of what transformations she has wrought on their bodies. Here, a set of enormous green claws dominate a much smaller body, with similarly large eyes set in the middle of a yellow and green circle of feathers, calling to mind the gawkiness of youth. Ashevak once called herself a happy owl, but to the best of our knowledge, never titled a work other than this with that adjective. We like to think this is a self-portrait.

Kenojuak Ashevak Illustrious Owl (1999)

ILLUSTRIOUS OWL (1999)

Hoo do you think you are? By the time Ashevak released this print, she was already a Companion of the Order of Canada, had been elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and received two honorary doctorates from Queens and the University of Toronto. Her pearls of wisdom gather around Illustrious Owl, illuminating its black body with shades of rusty red, moody purple and saffron yellow.

Kenojuak Ashevak Inquisitive Owl (2001)

INQUISITIVE OWL (2001)

I say hooom, not hoo, when I ask questions. Ashevak’s Inquisitive Owl is thinking so hard that questions are literally coming out the top of its head. The contained orange body, boundaried on either side by black and red wings, is juxtaposed with the wild spring flowing from the head, navy thoughts exploding upwards and outwards.

Kenojuak Ashevak Long Feathered Owl (1994)

LONG FEATHERED OWL (1994)

The Long Feathered Owl really shows off Ashevak’s masterful skill of balancing. The long blue feathers of this owl are perfectly mirrored on either side of the owl, keeping the deep maroon coloured bird standing tall.

Kenojuak Ashevak Lustrous Owl (2012)

LUSTROUS OWL (2012)

Glowy and flowy, Lustrous Owl was one of Ashevak’s last prints before her death in 2013. The etching/aquatint method Ashevak used here imparts a smooth transition between colours, light and dark, making the owl appear lit from within. Although Ashevak features spreading feathers in many of her depictions of owls, in a flight of imagination here she has opted to preserve the radial symmetry and tip the feathers with yellow, enhancing the owl’s resemblance to the sun.

Kenojuak Ashevak Majestic Owl (2011)

MAJESTIC OWL (2011)

Look no feather than Majestic Owl if you would like an optical illusion. The red shafts of the owl’s plumage emanate from its black body and expand into tufted black ends with inverted arrow points, creating a Muller-Lyer illusion that bounces the eye outward as it travels around the image. Uninterrupted by the owl’s body or other elements on the page, Ashevak’s deceptively simple linework traps the viewer in feathers until their gaze is broken.

Kenojuak Ashevak Observant Owl (2009)

OBSERVANT OWL (2009)

In Observant Owl, the owl gazes openly upon the viewer, as if aware of its own strange majesty. A stonecut and stencil work from later in Ashevak’s life, it showcases the newer printmaking techniques that allowed her to create the fine textures on the bird’s gray-green body as well as the striking transition of the feathers from incandescent yellow into earthy red. The print was featured in the “Nipirasait: Many Voices” (2010) at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC, an exhibition that celebrated five decades of Inuit art from Cape Dorset.

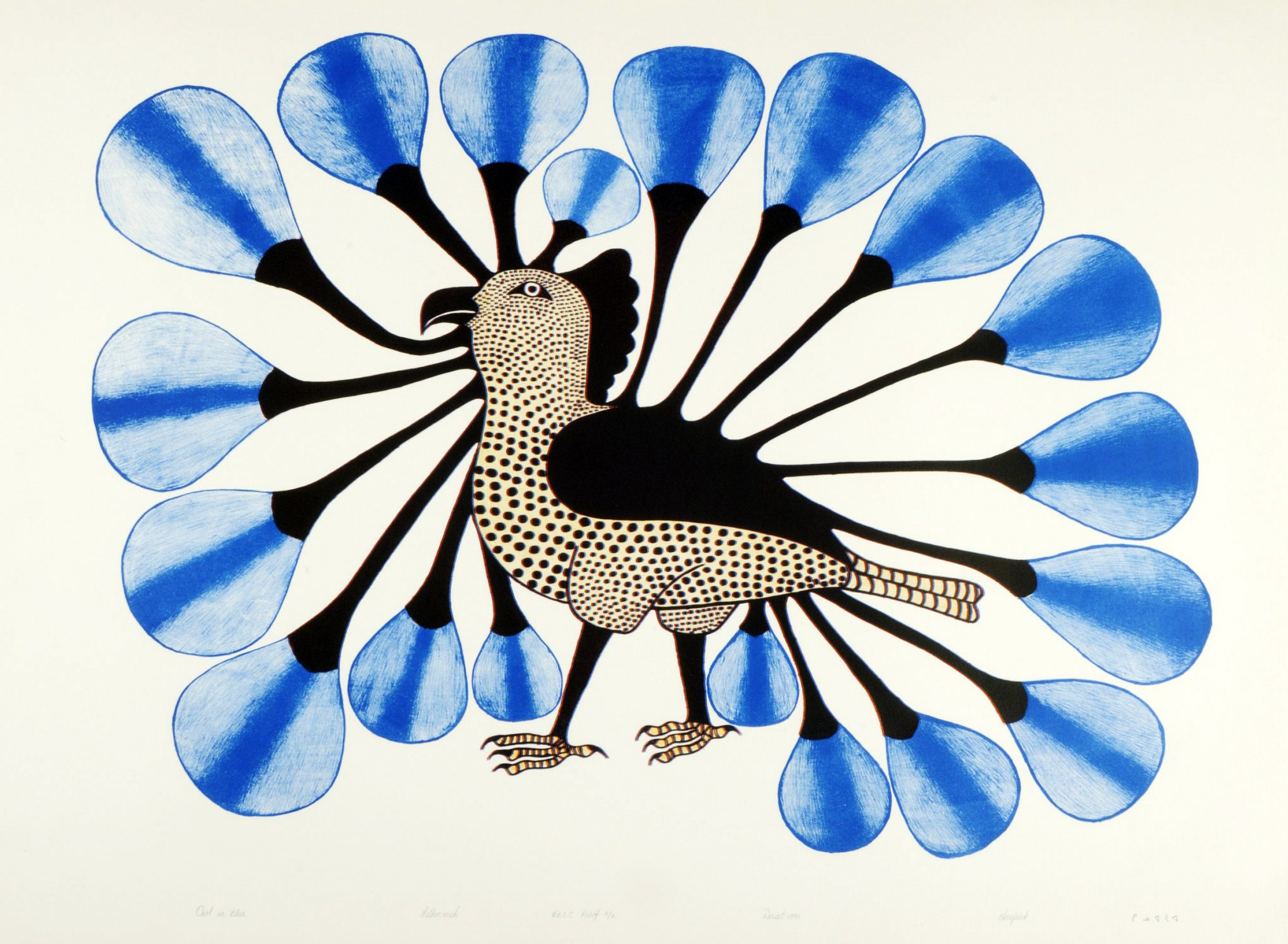

Kenojuak Ashevak Owl in Blue (1991)

OWL IN BLUE (1991)

Picasso has his blue period, and Ashevak has hers. Far from depression, Owl in Blue seems almost celebratory in the exuberance of its plumage and its polka dot body, strutting across the page. The black shape protruding from the back of the head could easily be a cockscomb raised in pride as the only solo owl print Ashevak featured in the 1991 Cape Dorset Print Collection.

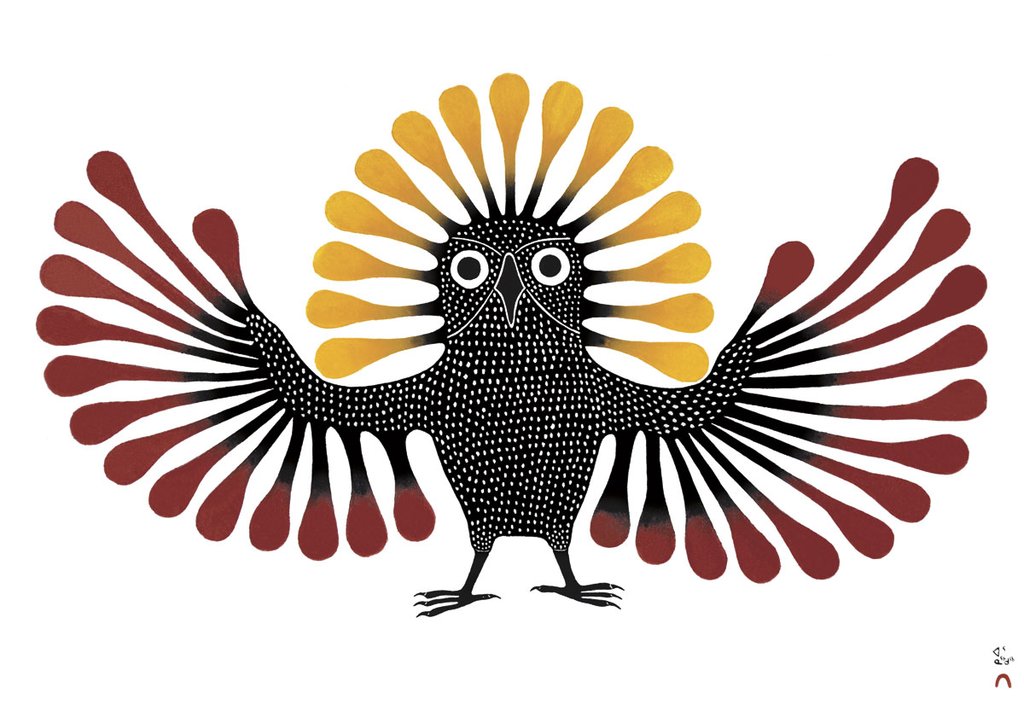

Kenojuak Ashevak Preening Owl (1995)

PREENING OWL (1995)

Preening has two meanings: to clean or straighten one’s feathers (as in a bird), or to congratulate or pride oneself. Ashevak’s Preening Owl, with its outstretched wings, full-frontal pose, and golden halo is clearly partaking in the latter. One wonders if Ashevak was taking a moment to take pride in her own work, or if she felt that any bird with a magnificent display of plumage such as this should justly be proud. Either way, Preening Owl, which was first featured in the 1995 Cape Dorset Print Collection, has become one of Ashevak’s most well-known and frequently reproduced prints.

Kenojuak Ashevak Proud Young Owl (1979)

PROUD YOUNG OWL (1979)

“I’m too cool for you.” – Proud Young Owl. This lithograph was one of the ten commissioned by Theo Waddington for the Waddington Galleries’ Ashevak portfolio, which was released in 1979. Many of the other works in the portfolio have Ashevak’s signature symmetry, with wide-eyed owls and outstretched plumage. This print, however, shows an owl turned partially away from the viewer, its wings outstretched, with narrowed eyes. Feathers were ruffled, literally and figuratively.

Kenojuak Ashevak Radiant Owl (1996)

RADIANT OWL (1996)

Whether shown in its green or orange variants, Radiant Owl is a sight to behold. The tawny feathers on the orange version are interpreted as a tawny body on the green variant. Too, the green variant clearly shows that the orange was printed on an already green body. One wonders if the body on the orange version, which initially reads as black, had a similar inverse printing of green over orange, which ended up with a radically different colour. Whether the variants were meant as inverted versions of one another or not, the interplay of colour on both truly make this owl shine.

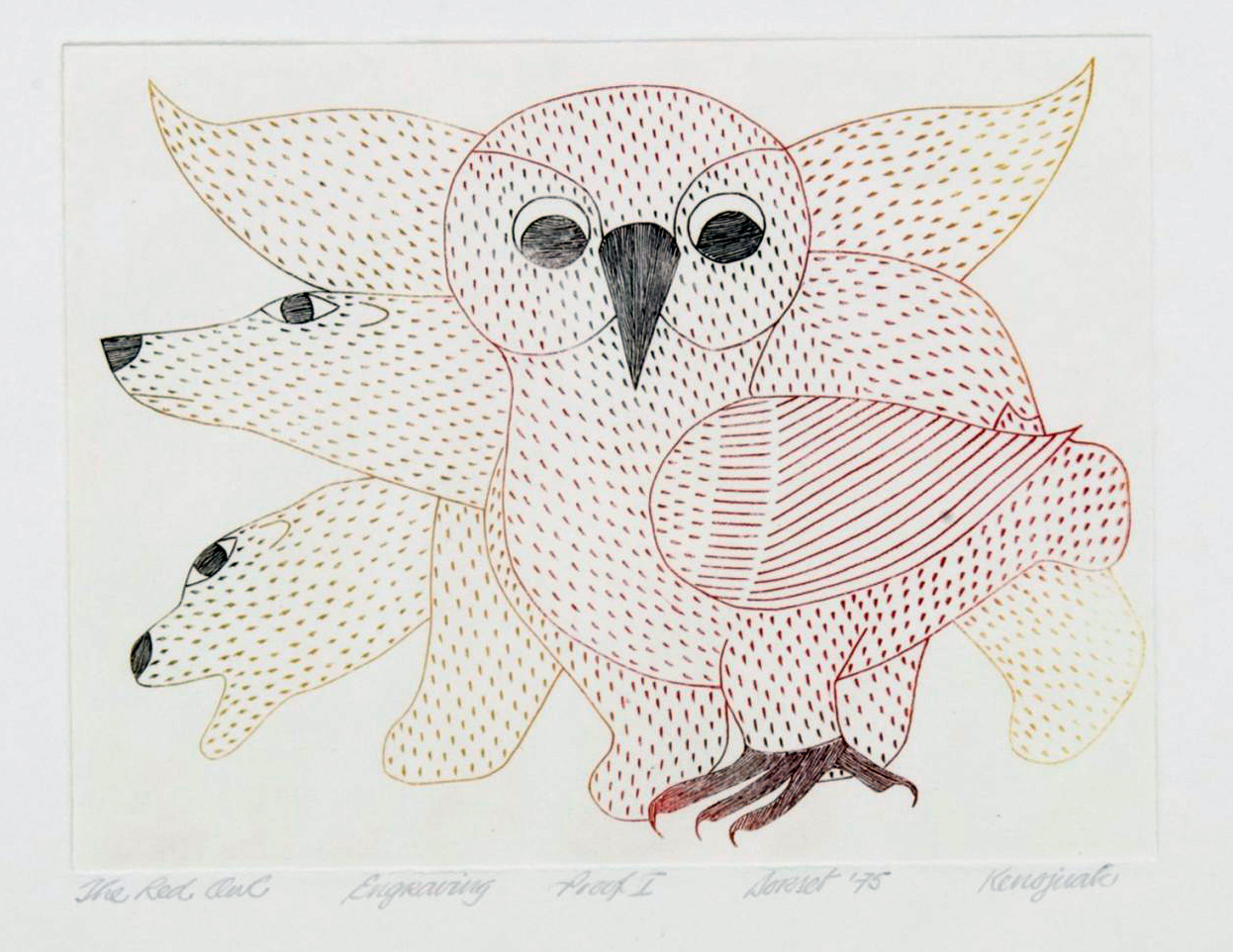

Kenojuak Ashevak The Red Owl (1995)

THE RED OWL (1995)

Just chillin’ with my polar bears. Ashevak’s The Red Owl became so celebrated following its release that it was featured on the April quarter for Canada’s 1999 millennium coin series, alongside Ashevak’s initials in syllabics, marking the first time syllabics appeared on circulation coinage. The owl dwarfs the polar bears in the background, commanding viewers with a direct gaze. In lieu of using colour to make the owl stand out, the Canadian Mint opted to make the owl shiny and background bears matte, retaining the parallel lines Ashevak drew for texture on both.

Kenojuak Ashevak Resplendent Owls (2005)

RESPLENDENT OWLS (2005)

One owl to bring them all and in the darkness bind them: resplendent means attractive and impressive, and these owls, with their clean lines and strong secondary colour palette, certainly are. Resplendent also, however, has monarchical connotations. Was Ashevak trying to establish a hierarchical relationship between these owls? The triangular composition, such a departure from the more circular one usually employed by the artist, and the purple colouring (long associated with royalty) on the top owl certainly suggests that this is the one owl to rule them all.

Kenojuak Ashevak Secluded Owl (2006)

SECLUDED OWL (2006)

Ashevak has barricaded her Secluded Owl in flowers, owl by itself. The symmetrical composition recalls the traditional decorative arts of Scandianvian countries, called Rosemåling, which incorporates flowers and scrollwork. Here, the leaves of Ashevak’s serigraph seem to fan out like the scrollwork of this traditional design method, although the mix of secondary colours in this depiction of a small owl with extravagant tail plumage is pure Ashevak.

Kenojuak Ashevak Sentinel Owl (1970)

SENTINEL OWL (1970)

Your perspective on Sentinel Owl will likely vary depending on whether or not you saw the restful print or its more elusive and energetic drawing. The print has a serenity that derives from the muted tones of red and purple which cover only certain aspects of leaves and wing, leaving the majority of the image to be represented by flowing black lines and negative space. By contrast, the drawing explodes off the page in a bright, high contrast rainbow that crowds for attention on a fully coloured image. Front and centre is the owl’s chest, smooth and white on the print, a saturated yellow with textural cross hatching on the drawing.

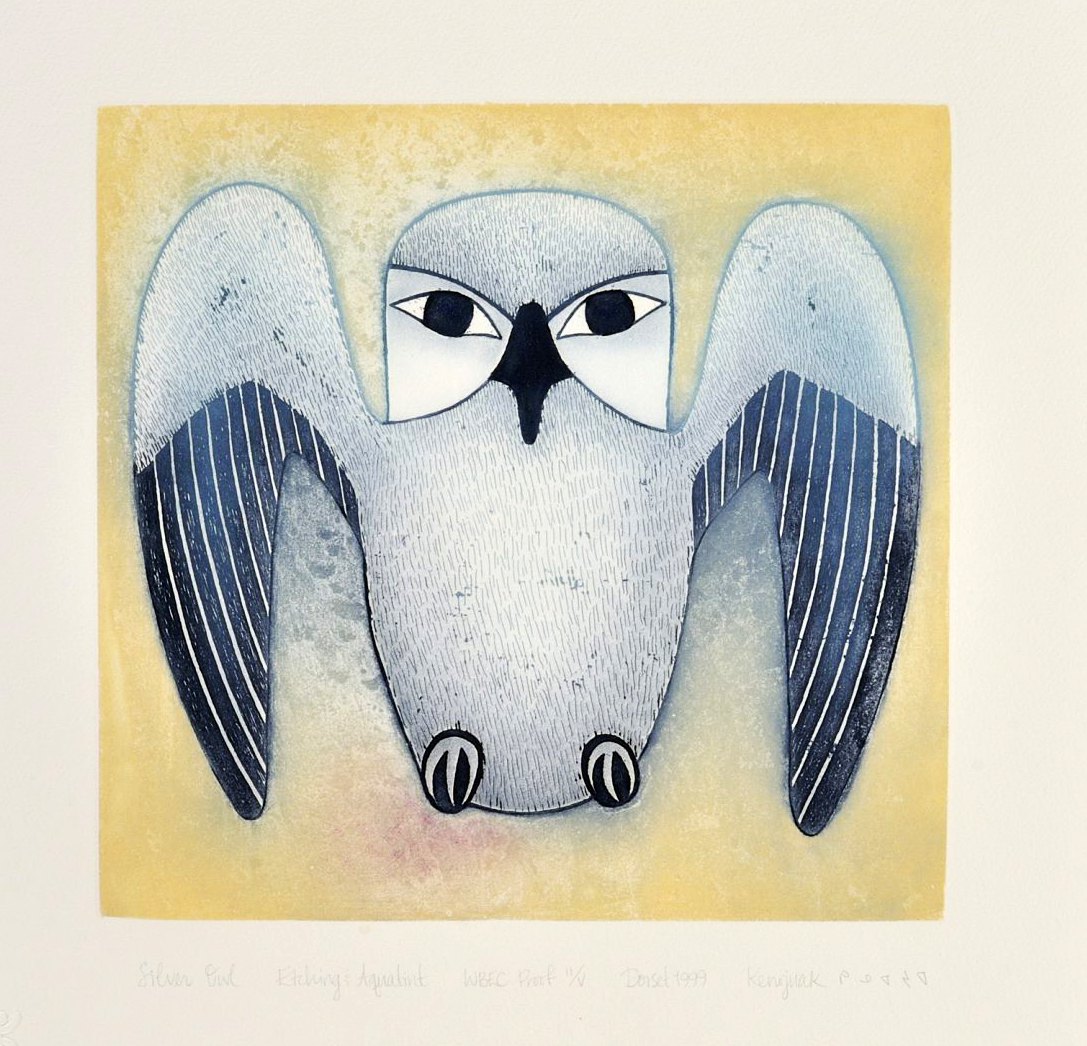

Kenojuak Ashevak Silver Owl (1999)

SILVER OWL (1999)

Silver Owl, which appeared in the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative collection, is a work of etching and aquatint, techniques that Ashevak experimented with in the last decade of her life. There is less of the imaginative colour play that we associate with her more eye-catching owls; instead, the silvery-purple palette of the bird’s body has an almost metallic sheen, which is softened by the watercolour effect created by the aquatint. The image is energized by her buoyant use of lines—the owl’s magnificent wings are dramatically raised as if it is about to take off.

Kenojuak Ashevak Singular Owl (2006)

SINGULAR OWL (2006)

It’s odd that Ashevak decided to call this work Singular Owl. This is one of many works by Ashevak where the owl appears alone, and in this case the viewer is granted a more expansive view of the background flora than usual, so the owl does not truly stand alone on the print. Further, this piece was produced around the same time as Secluded Owl (2006), and from the warm greens and oranges as well as the floral accoutrements, it’s clear that they are a pair. Birds of a feather flock together, don’t they?

Kenojuak Ashevak Solitary Owl (1998)

SOLITARY OWL (1998)

“Don’t call me, Owl call you” – Solitary Owl. Both literally and figuratively, this owl stands alone. It is the only object on the page, dominating the background with a blue that seems to emanate from its chest in a subtle glow. It is also one of the few examples of an Ashevak print with a dark background. Usually either left blank or else shaded with a primary colour, the deep brown printed onto the background gives a texture and interest needed in a print which features little in the way of other visual stimuli.

Kenojuak Ashevak Summer Owl (1979)

SUMMER OWL (1979)

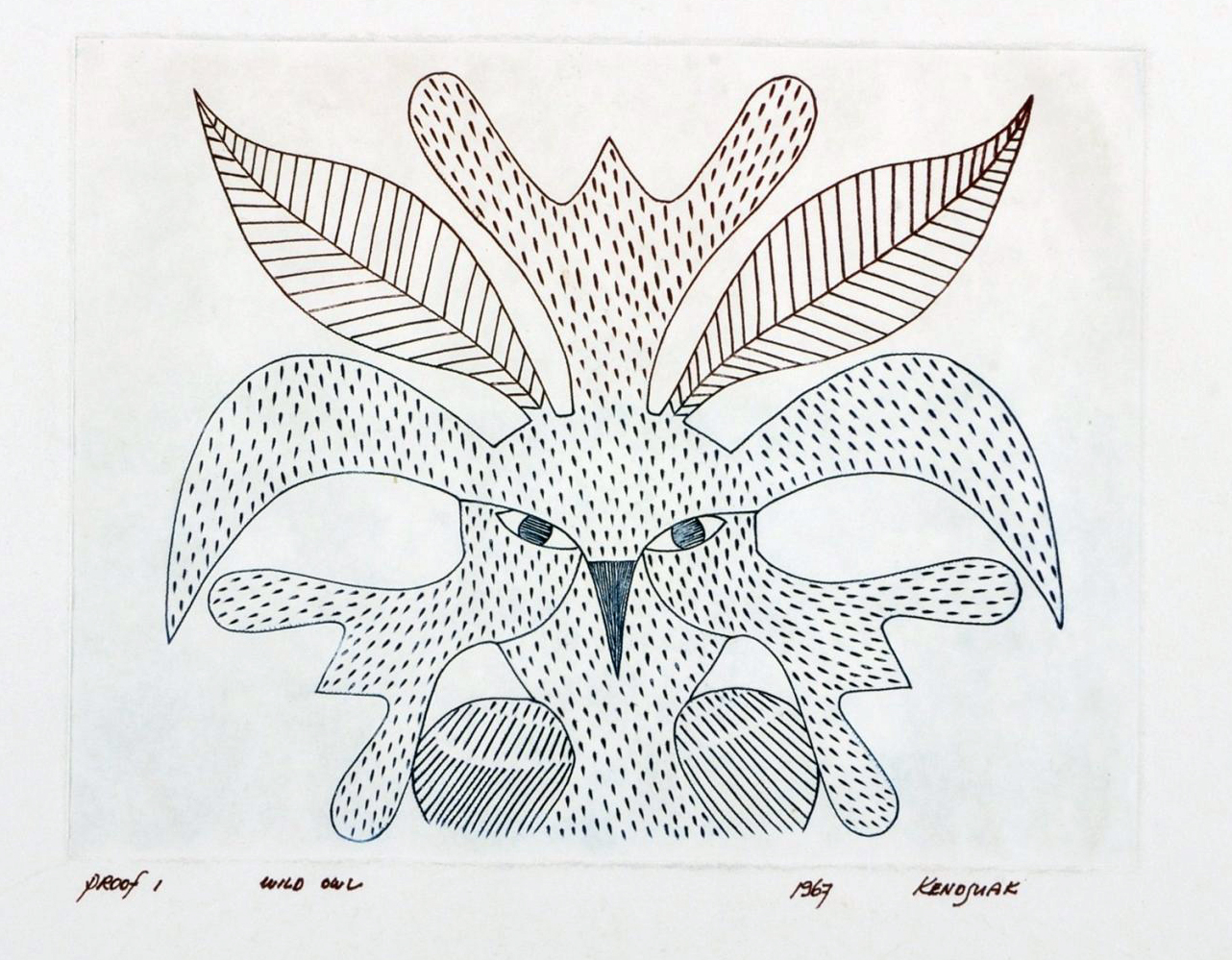

Kenojuak Ashevak Wild Owl (1967)

WILD OWL (1967)

“All good things are wild and free” says Henry David Thoreau, and Wild Owl is no exception. A flurry of antlers and leaves burst forth from the head of this staring animal, identifiable as an owl only by the eyes and beak, which remain constants regardless of how much Ashevak abstracts the owl itself.

Plague in Art: 10 Paintings You Should Know in the Times of Coronavirus

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Triumph of Death (detail), c. 1562, Museo del Prado, Madrid |

Source: DailyArt

March 9 2020

By Zuzanna Stanska

As the coronavirus is spreading around the globe we want to show you how artists depicted plague in art in times when plagues were really deadly.

I know it’s not comforting under current circumstances but actually, when you think about it, untreatable plagues were a regular part of human life for centuries. The medieval Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. It resulted in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. 200 million!

The 1918 an influenza pandemic known as Spanish flu (present from January 1918 to December 1920) infected 500 million people around the world. This amounts to 27% of the world population at the time. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million. 100 million! And it happened only one hundred years ago.

Or take HIV/AIDS, it is estimated that since the beginning of the epidemic in 1980s 75 million people have been infected with the HIV virus and about 32 million people have died of it. There is no cure or vaccine for it yet, however antiretroviral treatments can slow the course of the disease and lead to a near-normal life expectancy. Still, close to 13,000 people with AIDS in the United States are dying each year. The peak of this pandemic happened only thirty years ago.

We don’t know yet what would be the final numbers of coronavirus (also known as COVID-19) pandemia. Since the outbreak began in December 2019, 108,000 cases have been identified and 3,666 deaths have been reported. Also, 61,000 people have fully recovered (as of March 8th). So, please clean your hands (according to WHO it is the best way to prevent the coronavirus) and get ready for a short ride through art history and masterpieces you should know about in the times of Coronavirus.

1. Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead During the Black Death, 14th century

The Citizens of Tournai, Belgium, Burying the Dead During the Black Death of 1347-52. Detail of a miniature from The Chronicles of Gilles Li Muisis (1272-1352), abbot of the monastery of St. Martin of the Righteous, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, MS 13076-77, f. 24v.

In the time of the Black Death (1347 to 1351) themes such as skeletons, death, and the Dance of Death were very common in culture and especially art. There is no surprise here, it’s estimated that more than 30% of the European population died in the epidemic. In some cities, such as Venice, up to 60% of the inhabitants died. Also half of Paris’s population of 100,000 people died. Giovanni Bocaccio in his Decameron (1353) wrote:

“In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg … From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves.”Giovanni Bocaccio, Decameron, 1353.

Following this victims developed an acute fever and started vomiting blood. Most victims died two to seven days after initial infection.

Contemporary reports tell of mass burial pits dug in response to the large numbers of dead. Before 1350 there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany. By 1450 this number dropped by nearly 40,000 due to the Black Death. In this miniature we see how the citizens of Tournai, Belgium were burying the dead en masse. There are fifteen mourners and nine coffins all crammed into the small space. Interestingly the face of each mourner is given individual attention, each conveys genuine sorrow, and even more genuine fear.

In the time of the Black Death (1347 to 1351) themes such as skeletons, death, and the Dance of Death were very common in culture and especially art. There is no surprise here, it’s estimated that more than 30% of the European population died in the epidemic. In some cities, such as Venice, up to 60% of the inhabitants died. Also half of Paris’s population of 100,000 people died. Giovanni Bocaccio in his Decameron (1353) wrote:

“In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg … From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves.”Giovanni Bocaccio, Decameron, 1353.

Following this victims developed an acute fever and started vomiting blood. Most victims died two to seven days after initial infection.

Contemporary reports tell of mass burial pits dug in response to the large numbers of dead. Before 1350 there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany. By 1450 this number dropped by nearly 40,000 due to the Black Death. In this miniature we see how the citizens of Tournai, Belgium were burying the dead en masse. There are fifteen mourners and nine coffins all crammed into the small space. Interestingly the face of each mourner is given individual attention, each conveys genuine sorrow, and even more genuine fear.

2. Giacomo Borlone de Burchis, The Triumph of Death with The Dance of Death, 15th century

Giacomo Borlone de Burchis, The Triumph of Death with The Dance of Death, 15th century, Oratorio dei Disciplini in Clusone, Italy

The horror of the Black Death had another unexpected effect, very dark humor. The plague was often seen through a macabre and grim lens. The theme of The Dance of Death (Danse Macabre) is a great example of this. The earliest known appearances of it were in story-poems that told about encounters between the living and the dead. Most often the living characters were proud and powerful members of society, such as knights and bishops. The dead interrupted their procession: “As we are, so shall you be” was the underlying message, “and neither your strength nor your piety can provide escape”.

Clusone’s Dance of Death is a part of The Triumph of Death scene. It shows several characters from different social classes walking with skeletons to join the fatal dance of death. In The Triumph of Death Death itself is represented as a crowned skeleton queen swinging scrolls in both her hands. She has two fellow skeletons at her sides killing people with a bow and an ancient arquebus. Around her a group of powerful but desperate people are offering valuables and begging for mercy. Death is not interested in their mundane wealth however, she only wants their lives. Beneath her feet is a marble coffin where the corpses of an emperor and a pope lie surrounded by poisonous animals, symbols of a fast and merciless end.

The horror of the Black Death had another unexpected effect, very dark humor. The plague was often seen through a macabre and grim lens. The theme of The Dance of Death (Danse Macabre) is a great example of this. The earliest known appearances of it were in story-poems that told about encounters between the living and the dead. Most often the living characters were proud and powerful members of society, such as knights and bishops. The dead interrupted their procession: “As we are, so shall you be” was the underlying message, “and neither your strength nor your piety can provide escape”.

Clusone’s Dance of Death is a part of The Triumph of Death scene. It shows several characters from different social classes walking with skeletons to join the fatal dance of death. In The Triumph of Death Death itself is represented as a crowned skeleton queen swinging scrolls in both her hands. She has two fellow skeletons at her sides killing people with a bow and an ancient arquebus. Around her a group of powerful but desperate people are offering valuables and begging for mercy. Death is not interested in their mundane wealth however, she only wants their lives. Beneath her feet is a marble coffin where the corpses of an emperor and a pope lie surrounded by poisonous animals, symbols of a fast and merciless end.

3. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Triumph of Death, c. 1562

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Triumph of Death, c. 1562, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

We are not in the Middle Ages anymore but The Triumph of Death by Flemish Renaissance master Pieter Bruegel the Elder with a very deadly swing shows how the Black Death could look like in an average European town. OK, maybe I’m exaggerating a little, but an army of skeletons wreaking havoc across a blackened, desolate landscape makes a huge impression to this day. Fires are burning in the distance, the sea is full of shipwrecks. Everything is dead, even the trees and the fish in a pond. This painting depicts people of all social backgrounds, from peasants and soldiers to nobles as well as a king and a cardinal. Death takes them all indiscriminately.

4. Paulus Furst of Nuremberg, Doctor Schnabel von Rom, 1656

Paulus Furst of Nuremberg, Doctor Schnabel von Rom, 1656, British Museum, London.

The Black Death was more than a medieval horror, it kept coming back. For more than the next 300 years the plague became a regular part of everyday life in Europe. Terrible outbreaks periodically devastated cities. Look at this this way, the whole story of Europe between 14th to the late 17th century was constantly marked by the plague. Some great artists, probably including Hans Holbein and Titian, died of it. Meanwhile others tried to fight it with art, like Tintoretto. He painted his greatest works in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice, a building dedicated to a plague-protective saint. Death from the plague was a regular part of human life at the time.

In this etching we see a protective costume used in France and Italy in the 17th century. It terrified people because it was a sign of imminent death. It consisted of an ankle-length overcoat, a bird-like beaked mask, along with gloves, boots, a wide-brimmed hat, and another over-clothing garment. The mask had glass openings in the eyes and a curved beak shaped face with straps that held the beak in front of the doctor’s nose. The mask also had two small nose holes and was a type of early respirator which held sweet or strong smelling substances (usually lavender). The beak could also hold dried flowers, herbs, spices, camphor, or a vinegar sponge too. The purpose of the mask was to keep away bad smells, known as miasma, which were thought to be the primary cause of the disease. Germ theory later disproved this.

5. Arnold Böcklin, Plague, 1898

Arnold Böcklin, Plague, 1898, Kunstmuseum Basel.

Plague exemplified Arnold Böcklin’s obsession with nightmares of war, pestilence, and death. Böcklin was a Symbolist and here his personification of Death rides on a winged creature, flying through the street of a medieval town. According to art historians he took inspiration from news about the plague appearing in Bombay in 1898. Although there is no straightforward, visible evidence of Indian inspiration (Symbolists always used as ambiguous and universal symbols as possible) Böcklin created a scene that the creators of the Game of Thrones would not be ashamed of.

7. Egon Schiele, The Family, 1918

Egon Schiele, The Family, 1918, Belvedere, Vienna.

The 20th century brought two World Wars, the Holocaust, unimaginable atrocities, and the Spanish Flu. The horrific scale of this pandemic is hard to fathom. The virus infected 500 million people worldwide and killed an estimated 100 million victims. For perspective that’s more than all of the soldiers and civilians killed during World War I combined.

It had symptoms of a normal flu: fever, nausea, aches and diarrhea. Many developed severe pneumonia as well. Also dark spots would appear on the cheeks and patients would turn blue, suffocating from a lack of oxygen as their lungs filled with a frothy, bloody substance. Unlike a typical flu where the highest mortality is in infants and the elderly, the 1918 flu also struck down young, healthy adults.

Egon Schiele was one of the great artists who died from it. The Family was unfinished at the time of Schiele’s death and initially was titled Squatting Couple. It was one of his last paintings. In it we see Schiele himself with his wife Edith and their unborn child. In his last letter he described his concern for her writing “Dear Mother Schiele, Edith got the Spanish Flu eight days ago and has pneumonia. She is six months pregnant. The disease is very serious and life-threatening; I am preparing myself for the worst”. Edith died of Spanish flu in the 6th month of her pregnancy. Three days after she died Egon did too.

8. Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait after Spanish Influenza, 1919

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait After Spanish Influenza, 1919, Oslo, at the National Gallery.

Among other famous artists who died of the Spanish flu were Gustav Klimt, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, and Niko Pirosmani. Spoiler Alert: Edvard Munch caught it but he survived. Munch painted this work in 1919. He created a series of studies, sketches, and paintings, where in a very detailed way he depicted his closeness to death. As we see here, Munch’s hair is thin, his complexion is jaundiced, and he is wrapped in a dressing gown and blanket.

By the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic had come to an end. Those that were infected had either died or had developed immunity.

9. Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear 1989

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear, 1989, Poster Collection Noirmontartproduction, Paris.

In the 1980s and early 1990s the outbreak of HIV and AIDS swept across the United States and rest of the world. The disease originated decades earlier though. Today, over 70 million people have been infected with HIV and about 35 million have died from AIDS since the start of the epidemic. The virus is transmitted through bodily fluids such as blood, semen, vaginal fluids, anal fluids, and breast milk. In 1980s the public considered AIDS a “gay disease”, it was even called the “gay plague” for many years. Historically HIV spread from person to person through unprotected sex, sharing of needles for drug use, and through birth.

Keith Haring designed and executed this poster in 1989 after he was diagnosed with AIDS the previous year. In 1989 one American was diagnosed with HIV every minute and four people died of AIDS every hour. By 1991 the epidemic had claimed the lives of 100,000 Americans. The poster depicts three figures gesturing “see nothing, hear nothing, say nothing”. This implied the struggles faced by those living with AIDS and the challenges posed by individuals or groups that fail to properly acknowledge and respect the epidemic. The state of information about AIDS/HIV in United States 1980s was truly horrendous. At the time disinformation was common, the American government’s response to what was happening was shamefully inadequate, and the medicines and medical care were extremely expensive. People infected with HIV were left by themselves.

Keith Haring died of AIDS in 1990 at the age of 31.

10. David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Falling Buffalos), 1988-1989

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Falling Buffalos), 1988-1989, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Falling Buffalos) is one of the artist’s best-known works and perhaps one of the most haunting artistic responses to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. In this photo-montage we see a herd of buffalo falling off a cliff to their deaths. The falling buffalos evoke feelings of doom and hopelessness, making the work extremely powerful and provocative. Made in the wake of the artist’s HIV-positive diagnosis, Wojnarowicz’s image draws a parallel between the AIDS crisis and the mass slaughter of buffalos in America in the nineteenth century. It reminds viewers of the neglect and marginalization that characterized the politics of HIV/AIDS at the time. You can read how he manifested his outrage in the times of HIV/AIDS pandemic here.

Wojnarowicz died of HIV/AIDS in 1992.

<-- nd--="">

No comments:

Post a Comment