Πηγή: Truthout

By Mark Karlin

April 8 2012

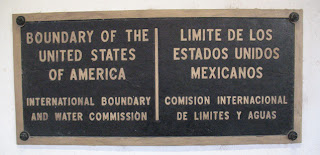

This is the third article in a Truthout series on viewing US immigration and Mexican border policies through a social justice lens, focusing on the lower Rio Grande Valley, Brownsville, Texas, area. Mark Karlin, editor of BuzzFlash at Truthout, visited the region recently to file these reports. The first two installments in the series are, "The Border Wall: The Last Stand at Making the US a White Gated Community" and "Murder Incorporated: Guns, the NRA and the Politics of Violence on the Mexican Border."

The Official Story From the US State Department

On March 29, 2012, William R. Brownfield, US assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (in other words, Hillary Clinton's point person on drug issues), testified before the House Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs. His subject was the war on drugs in the Western Hemisphere outside of the United States and Canada. Few, if any, reporters from the US press attended.

Approximately 50,000 or more Mexicans have been killed since Mexican President Felipe Calderon launched a so-called war on drug cartels. (In a recent appearance in Toronto, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta claimed 150,000 people have died in the drug war in Mexico, but the timeline Panetta was referring to was unclear, as was the origin of the figure he cited.) Given that five Juarez police officers were gunned down at a party the night before Brownfield's testimony, the Spanish-language press, unlike the American media, took an interest in his remarks.

You see, Juarez is kind of a sore spot for Mexicans. In 2010, more than 3,000 homicides took place in the city where killings are committed with general impunity, making it the murder capital of the world that year. Although Juarez's murder rate has now lowered slightly, the city's mayor - who lives across the Rio Grande in El Paso, Texas - indignantly denies that Juarez is the deadliest city on earth, even though it almost certainly remains close to being just that. Borderland writer Charles Bowden writes in "Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the Global Economy's New Killing Fields": "The violence is everywhere. It is like the dust in the air, part of life itself."

In his statement, Brownfield provided the US House of Representatives with the usual litany of claimed successes, but he also made a few observations that say much about the failure of the US war on drugs south of the border. (Brownfield argues that the Merida Initiative, as the US drug war's counterpart in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean was named by its US funders, is having a positive impact.)

As in the United States, Widespread Poverty and Unemployment Create a Fertile Marketplace for Illicit Drugs

In the subcommittee hearing, Brownfield admitted right off: "The persistently high homicide and crime rates throughout Central America, the Caribbean and the horrific reports of violence inside Mexico are symptoms of a broader climate of insecurity throughout the region. Crime and violence are exacerbated by widespread poverty and unemployment. This is brought into greater focus as criminal organizations react to the increasing pressure placed on their operations by governments in the region with support from the United States."

The high poverty rate is also the major reason why so many Mexicans try to migrate to the United States, but several hundred thousand of them a year are turned back, and an unknown number of them become victims of the hyperviolence brought on by the US/Calderon war on drugs.

Playing a Game of Deadly "Whack-a-Mole"

Next, Brownfield acknowledged that the US war on drugs in many of the southern nations of the Western Hemisphere is basically a bloody game of whack-a-mole. "In 2008, anticipating that Mexico's efforts to challenge cartels would result in the movement of trafficking routes elsewhere," said Brownfield, "the US government formed a partnership with Central American nations to enhance their security capacity."

The top US State Department official on drugs boasted that some drug kingpins - due to US-backed military and police action - were forced to move their operations to Mexico from Colombia and are now moving some of them to Central America. Then, Brownfield predicted that they will start using the Caribbean as a base. But what is lost in his testimony is that there is no measurable indicator that the supply of illicit drugs into the United States is decreasing as a result.

So, there is no end game here. The United States is using all its vast powers to do what urban police do in American cities: chase the corner drug dealers out of one area and into another, through the use of temporary intensive "enforcement" - and then chase them back again at a later date.

In a recent BuzzFlash at Truthout commentary, Bowden was quoted as writing: "There is a second Mexico, where the war is for drugs, for the enormous money to be made in drugs, where the police and military fight for their share - where the press is restrained by the murder of reporters - and feast on a steady diet of bribes, and where the line between the government and the drug world has never existed."

In the question-and-answer period after his testimony to Congress, Brownfield (as reported in the Spanish press and translated by Truthout) "emphasized that the infiltration of the crime organizations and of the narco-trafficking in the Mexican police is 'a very, very grave problem,' above all at the local and state level, now that the federal level of law enforcement corruption has diminished."

In Nearly Half of Mexico's States, Less Than 1 Percent of Crimes Resulted in Sentencing: 80-96 Percent of Killings Go Unpunished

The New York Times recently reported that, "in 14 of Mexico's 31 states, the chance of a crime's leading to trial and sentencing was less than 1 percent in 2010, according to government figures analyzed by a Mexican research institute known as Cidac. And since then, experts say, attempts at reform have stalled as crime and impunity have become cozy partners." According to Fox News Latino, 80-96 percent of the killings in Mexico go unpunished.

A Drug-Trafficking Free Market Paul Ryan Can Love

Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin), a devotee of Ayn Rand, can only love the tenacious entrepreneurialism of the government, military, law enforcement and cartel traffickers in Mexico. This is what supply-side economics is all about.

In an interview with Truthout, Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the influential Drug Policy Alliance, explained the futility of launching a war via the joint forces of military and law enforcement (particularly, Truthout independently maintains, given the endemic corruption in Mexico.)

"A law enforcement strategy cannot defeat a dynamic global commodities market," said Nadelmann. "The illegal drug market is very much the same as alcohol, food, etc. So as long as there is demand, there will be a supply. Attempts at interdiction just moves the drug trafficking around, wreaking havoc in its wake."

Promoting Legalization Can Make for Strange Bedfellows

Yes, Ryan would be pleased - were he forthright - to know that the late Milton Friedman advocated for the legalization of drugs that are currently contraband. In an interview in the early 90s, Friedman was eager to talk about the topic:

"The case for prohibiting drugs is exactly as strong and as weak as the case for prohibiting people from overeating," said Friedman. "We all know that overeating causes more deaths than drugs do. If it's in principle okay for the government to say you must not consume drugs because they'll do you harm, why isn't it all right to say you must not eat too much because you'll do harm?"

Friedman also noted that by not legalizing drugs, the United States is enabling massive corruption and the control of narcotics into the hands of more or less monopolistic entities: in the case of Mexico, a sort of battle for the marketplace among the cartels, the government, law enforcement and the military.

Supporters argue that Calderon, a member of the National Action Party (known by its Spanish initials, PAN), has continued an incremental break from the corrupting, single-party rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (known by its Spanish initials, PRI), in which the cartels, the government, the military and law enforcement had agreements on who would take which cuts of the drug money; as a result, argue Calderon's backers, there was less rampant violence. Such advocates of the Mexican president contend that he is breaking through decades of PRI corruption and slowly reforming basic state institutions, including a corrupt and inflexible judiciary and law enforcement system, which is detailed in the documentary film "Presumed Guilty."

But what does one then say about Noe Ramirez Mandujano, for instance? He served as Calderon's top anti-drug official for two years. Eventually, Ramirez was arrested, "on charges he accepted $450,000 a month in bribes from drug traffickers," according to CNN. "Ramirez was accused of meeting with members of a drug cartel while he was in office and providing information on investigations in exchange for the bribes."

The Tentative Revolt of South-of-the-Border Presidents Against the War on Drugs

The Washington Post reported that at a December meeting in Mexico City:

Latin American leaders have joined together to condemn the US government for soaring drug violence in their countries, blaming the United States for the transnational cartels that have grown rich and powerful smuggling dope north and guns south.

Alongside official declarations, Latin American governments have expressed growing disgust for US drug consumers - both the addict and the weekend recreational user heedless of the misery and destruction stemming from their pleasures.

Calderon has been tepidly testing the waters in challenging the United States (whether for domestic Mexican public relations purposes or as a real ultimatum to Washington DC is not clear) to address US domestic demand. "We are next to the largest illegal drug market in the world," Calderon said in September at a public dinner held in his honor by the Council of the Americas in Washington. "We are living in the same building, and our neighbor is the largest consumer of drugs in the world and everyone wants to sell him drugs through our door and our window."

Another group of Latin American leaders (from Guatemala, Panama and Costa Rica) recently held a mini-summit. The goal was to look for reducing the demand side in the United States as an alternative to the violence visited upon their nations by massive armed interdiction.

But the Central American leaders are treading cautiously because of their economic, political and military relationships with the United States. David Bacon, a regular author for Truthout on Mexican and Central American issues, notes that it is also important to see the US war on drugs as an extension of its foreign policy, particularly in the military arena.

Indeed, in 2011, The New York Times reported, "The United States is expanding its role in Mexico's bloody fight against drug trafficking organizations, sending new CIA operatives and retired military personnel to the country and considering plans to deploy private security contractors in hopes of turning around a multibillion-dollar effort that so far has shown few results."

For years, the United States has held the marionette strings on Latin American armies, moving their puppets via military aid, training armed forces leaders through what was then named the School of the Americas (now the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), the backing of right-wing death squads (often affiliated with national armies) and the provision of counterinsurgency advisers, to name a few methods of asserting military hegemony in the Western Hemisphere, apart from Canada.

That brings us back to the so-called war on drugs in Mexico.

In an article in The Nation, Bowden and borderland researcher-expert Molly Molloy explain what they believe is happening in Mexico as thousands die and disappear while the US press all but ignores the situation:

Calderón's war, assisted by the United States, terrorizes the Mexican people, generates thousands of documented human rights abuses by the police and Mexican Army and inspires lies told by American politicians that violence is spilling across the border (in fact, it has been declining on the US side of the border for years).

...

We are told the Mexican Army is incorruptible, when the Mexican government's own human rights office has collected thousands of complaints that the army robs, kidnaps, steals, tortures, rapes and kills innocent citizens. We are told repeatedly that it is a war between cartels or that it is a war by the Mexican government against cartels, yet no evidence is presented to back up these claims. The evidence we do have is that the killings are not investigated, that the military suffers almost no casualties and that thousands of Mexicans have filed affidavits claiming abuse, often lethal, by the Mexican army.

Here is the US policy in a nutshell: we pay Mexicans to kill Mexicans, and this slaughter has no effect on drug shipments or prices.

There is an exception to this last point, as CNN notes, because the shipments and profits increase, even as the quality of the drugs go up and wholesale price per kilo decreases - the free market at work.

Molloy is a librarian at the New Mexico State University in Las Cruces who has taken it upon herself to chronicle the endless ledger of the dead in Juarez in her Frontera listserv. In Mexico, there is a celebration in November called Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, to honor the spirits of the dead. For years, by highlighting news articles and commentaries about their deaths, Molloy has ensured that those who are killed in Juarez are listed on her project, that they are remembered, so that their souls are not lost in the purgatory of the forgotten. Yet many escape Molloy's chronicles because they are killed anonymously and buried in the desert or in houses turned into clandestine cemeteries. These victims are the vanished.

Molloy's is a grim task, but it is an act of mercy to the memories of those who are brutally killed - and an effort to help create, by bearing witness to a killing field, an end to the horror.

Meanwhile, in the United States, controlling the demand side appears to be interpreted as throwing people - particularly minority men - in jail for drug offenses, leading to the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Yet, the consumer market for illegal drugs continues unabated in the United States, as does the supply. Ryan might - were he ideologically honest - be the first to tell you that, when there is a $50 billion demand (perhaps as high as $100 billion or more in North America as a whole), the product will make its way to market one way or another.

As it does.

No comments:

Post a Comment